Mariana Lopes de Araújo

Lucas Soares Caldas

Lucas Soares Caldas

Bruna Stamm Barreto

Bruna Stamm Barreto

Pedro Paulo Murce Menezes

Pedro Paulo Murce Menezes

Júlia Cássia dos Santos Silvério

Júlia Cássia dos Santos Silvério

Laís Campos Rodrigues

Laís Campos Rodrigues

André Luiz Marques Serrano

André Luiz Marques Serrano

Clóvis Neumann

Clóvis Neumann

Nara Mendes

Nara Mendes

Graduate Program in Administration—PPGA, University of Brasília, Brasilia 70910-900, Brazil Author to whom correspondence should be addressed. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14(6), 117; https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14060117Submission received: 4 April 2024 / Revised: 9 May 2024 / Accepted: 24 May 2024 / Published: 3 June 2024

The purpose of this study is to propose an integrative model for evaluating the effectiveness of performance management system (PMS). This model aims to systematize the dimensions and criteria used in the literature and provide clarity in terms of evaluation possibilities. A comprehensive review of the literature was conducted to identify the dimensions, criteria, and causal relationships used in evaluating PMS effectiveness. A sample of 57 articles was analyzed using content analysis. The study established dimensions and criteria that have been neglected in the literature. The review resulted in the proposal of an integrative model for evaluating PMS effectiveness, which incorporates individual and organizational dimensions and criteria identified in the literature. It sheds light on recurrently adopted dimensions, particularly those related to individual-level phenomena, and seeks to clarify current conceptual ambiguities. This study’s originality lies in its integrative approach, which diverges from the prevailing tendencies in the field. This study provides clarity regarding the conceptual confusion surrounding ambiguous concepts and generically applied measures that hinder the drawing of certain conclusions about the effectiveness of PMS.

Performance management systems (PMSs) have garnered attention from both theorists and practitioners in recent years due to their principles that address the organizational aspirations of a Human Resource Management (HRM) unit’s ability to strategically contribute to the organization by aligning organizational goals with individual employee performance. Despite a growing body of research focusing on PMS modeling and psychometrics, as well as efforts to conceptually differentiate performance appraisal (PA) from performance management (PM), both are still perceived as flawed by employees and managers (e.g., Ikramullah et al. 2016; Murphy 2020).

Merely making technical or methodological adjustments to PMS is not enough to change people’s perceptions of them (Levy et al. 2017), so it remains a practice that has fallen short of organizational expectations (Cappelli and Conyon 2017). As a result, scholars and practitioners have questioned whether the investments made to implement and promote performance management truly yield substantial benefits for organizations (Awan et al. 2020; Cappelli and Conyon 2017; Garengo et al. 2022; Ikramullah et al. 2016; Iqbal et al. 2019; Kakkar et al. 2020; Keeping and Levy 2000; Lawler 2003; Modipane et al. 2019; Schleicher et al. 2019; Sharma et al. 2021).

Demonstrating the effectiveness of PMS is a more complex and challenging task than assessing the effectiveness of other organizational activities (Ahmed 1999). Thus, recent research has focused on investigating the effectiveness of PMS using specific measurement criteria to assess antecedent-outcome relationships that demonstrate performance management effectiveness (Iqbal et al. 2015).

However, the number of studies that are applied in isolation and without a comprehensive approach hinders the development of scientific and practical advancements. Theoretically based objective criteria should provide contributions to identifying the effectiveness of PMS. The absence of a systematic approach to criteria is reflected in the methodological operationalization of studies, which often adopt general measures that make it impossible to reach specific conclusions regarding the effectiveness of PMS (Schleicher et al. 2019). This need for greater clarity to address conceptual confusion was pointed out as early as 1995 by Murphy and Cleveland, but it still persists, as noted by authors such as Schleicher et al. (2019).

Therefore, a question remains regarding the capability of PMS as a tool for promoting better individual behavior that can foster organizational performance. Thus, there is a need for studies that address these concerns and provide a new integrative approach that goes beyond the universalistic tendency of the field and expands the development of theories focused on the specific field of HRM. These studies should also address the needs of practitioners by offering insights into the outcomes of PMS that cater to the interests of HR departments through an applied approach.

The purpose of this paper is to propose an integrative model to evaluate the effectiveness of performance management systems (PMSs) by systematizing the dimensions and criteria adopted by the literature in the field. Based on this, it will be possible to address the authors’ demands regarding the description of evaluation possibilities, outlining those that are more established and those that have been neglected by the PM literature, and promoting a streamlined and theoretically robust model for evaluating the effectiveness of PM. Furthermore, this investigation aims to demonstrate the Impact of PMS on organizational perspective variables as well, providing clearer answers to doubts regarding the adoption of PMS.

In the 1980s, the globalized international market led to increased organizational competition, which prompted a shift in focus from traditional advantages to the strategic role of “people” as a key resource (Becker and Huselid 1998). This shift extended the analysis of HR practices from individual to organizational levels, emphasizing HR systems and their alignment with organizational strategy (Wright and Ulrich 2017).

This evolution gave rise to Strategic Human Resource Management (SHRM), where human resources became a significant source of competitive advantage (Guest 1987; Jackson and Schuler 1995). The strategic nature of HRM has been defined and refined over the years from various perspectives (Boxall and Purcell 2000; Jackson et al. 2014; Wright and McMahan 1992). Notably, SHRM is described as the study of HR systems and their interrelationships with the organizational system, as well as other elements related to the organizational system, such as the internal and external environment, and the various stakeholders that interact with HR systems as well as other stakeholders, in order to evaluate organizational effectiveness and determine long-term survival (Jackson et al. 2014).

Given that HRM strategic practices are usually designed to promote organizational performance as a general objective, evaluating the effectiveness of HRM involves assessing this multidimensional construct, which makes measurement problematic (Baird 2017; Huselid 1995). Beyond this general objective of the HRM system, it should be clear that there are also specific objectives that vary depending on the needs, values, and preferences of stakeholder groups, making it more difficult to reach a consensus on which objective would be useful for determining the effectiveness of the HRM system (Colakoglu et al. 2006). Therefore, it is assumed that there is no exclusive criterion or one that is more important due to the reasons explained earlier.

This reinforces the need to investigate multiple criteria, considering the interrelationship between them as well as the position occupied by each, with some being more proximal and others more distant from HRM practice (Colakoglu et al. 2006; Ikramullah et al. 2016). However, most studies still focus on internal outcomes, even though there is a need to consider this holistic view in which both internal and external aspects of the organization are considered (Jackson et al. 2014). In this sense, it has been concluded that a set of interconnected HRM practices rather than those in isolation are more likely to produce superior performance (e.g., Huselid 1995).

In this regard, this research investigates HRM as a structuring system of organizational HRM strategic decisions through the interconnection of different subsystems and HRM practices in order to maximize organizational results (Den Hartog et al. 2004; DeNisi and Pritchard 2006). The relationship between HRM and performance is evident when using HR metrics; however, many of the research challenges outlined in the HRM and performance area are also perceived when considering HR metrics.

Within SHRM, a crucial focus on actively assessing and managing organizational and individual performance emerged to promote effectiveness (Brown et al. 2019; Den Hartog et al. 2004). Initial studies, predating 1920, primarily emphasized performance evaluations rather than actual performance management (Den Hartog et al. 2004; DeNisi and Pritchard 2006).

While performance appraisal (PA) and performance management (PM) may seem similar, recent studies have differentiated them (DeNisi and Murphy 2017). PA is a formal, typically annual event that does not include continuous feedback and alignment with business goals. PM is a continuous process that encompasses various activities, including goal-setting, execution, monitoring, and reviewing (Armstrong 2015).

PM serves multiple purposes and aids in decision-making for performance-based pay, training, development, and workforce planning (Aguinis 2013). Despite disagreements regarding the scope of the PM model, there is a consensus on viewing PM as a system where interconnected elements influence each other (Schleicher et al. 2018).

Despite widespread adoption, PM faces criticism from employees, with concerns being raised about its effectiveness (DeNisi and Murphy 2017; Schleicher et al. 2018). Levy et al. (2017) argue that managing individual performance has not worked well, which has prompted a reconsideration of this approach. Questions persist about the substantial benefits of PM investments in organizations (Murphy 2020), raising doubts about the effectiveness of many PM systems (Armstrong 2015; Schleicher et al. 2018).

A common complaint among employees regarding PM (Murphy 2020). Levy et al. (2017) state that managing individual performance has not been effective in organizations, and although this has been known for some time, it is only now that practitioners and academics are seeking a change in approach. In this regard, the actual consequences of what was prescribed by the PM literature have been questioned, and despite considerable progress in establishing the relationship between HRM and performance, theoretical and empirical issues persist (Baird et al. 2022).

Although the effectiveness of PMS can be defined as the alignment between employees and organizational goals (Armstrong 2015), it is not as simple as it seems (Ahmed 1999). The effectiveness of PMS has been investigated using certain measurement and outcome criteria to assess the antecedent-result relationships that manifest PM effectiveness (Iqbal et al. 2015). Therefore, attention over time has shifted towards different evaluation criteria, such as evaluation errors, utilization, and social context, among others (Keeping and Levy 2000). There is also a recurring use of the same criteria in studies, such as financial indicators or the perception of PMS, representing a reaction dimension, which has resulted in a disproportionate focus on certain adopted criteria (Schleicher et al. 2019). Recent criticism has also focused on the lack of interaction among these criteria (Ikramullah et al. 2016; Schleicher et al. 2019). The studies that point out this gap are the same that have sought to fill it by establishing integrative models for evaluating PM effectiveness, complementing the field with other theoretical perspectives.

This is the case with the performance evaluation effectiveness model proposed by Levy and Williams (2004). The authors conducted a review of the literature to identify aspects related to the Social Context Theory (SCT), which discusses the influence of social context on organizational practices and policies. The social context in which performance evaluations take place plays a key role in the effectiveness of the evaluation process, influencing how evaluation participants react to it. The authors’ proposed model for evaluating effectiveness is based on the reactions of evaluation participants, which was aligned with a growing number of studies at the time that emphasized the importance of reactions as evaluation criteria. In addition, the authors considered evaluator errors and biases, as well as evaluation accuracy, as criteria for evaluating the effectiveness of performance evaluations.

Iqbal et al. (2015) proposed an integrative model that also focuses on the reactions of those being evaluated to assess the effectiveness of performance evaluations. The model was developed based on the emphasis given by certain studies that focus on the reactions of those being evaluated. The proposed model is discussed in four parts. The first three parts discuss the relationships between the measurement criteria and the rater reactions (purpose, accuracy, and fairness). The fourth part discusses the ratee reactions (Iqbal et al. 2015). The interpretation used to develop the model provides empirical and theoretical-rational evidence that the evaluation effectiveness criteria are related to the reactions of those being evaluated.

The effectiveness evaluation model proposed by Ikramullah et al. (2016) utilizes the Competing Values Framework (CVF). The CVF was developed by organizational researchers to demonstrate factors that influence organizational effectiveness. It consists of three dimensions of competing values in opposing quadrants: internal vs. external, control vs. flexibility, and means vs. ends (Ikramullah et al. 2016). Inspired by the CVF, the authors propose internal processes, human relations, open systems, and a rational goal model as important aspects for evaluating the effectiveness of performance evaluation/management.

The most recent model was proposed by Schleicher et al. (2019) and is based on a theoretical-conceptual review of the last 30 years of scientific production on performance evaluation/management, including both empirical and conceptual research with academic and practical perspectives, to obtain an overview of the criteria used to measure and discuss the effectiveness of performance evaluation/management. Thus, the authors propose a comprehensive model that considers three aspects: (a) the existing content in the evaluation field; (b) criteria of interest to practitioners and academics; and (c) constructs on the micro- and macro-organizational levels.

Despite these models, there is a lack of integration among the accumulated studies in terms of the evaluation of performance evaluation/management, which hinders the development of both the scientific and practical fields due to the absence of objective theories and methods with criteria that truly identify their effectiveness. Thus, the systematization of production makes it possible to reflect on the possibilities of criteria for evaluating the effectiveness of performance evaluation/management, outlining those that are more consolidated as well as those that are still marginalized by the literature but are necessary for understanding its effectiveness.

A systematic review of the literature was conducted, focusing on the criteria used to evaluate the effectiveness of PMS in the following databases: Scopus, the Web of Science (yielding results only for English descriptors), Scielo, Spell, Periódicos Capes, and Google Scholar (for results in Portuguese). The search was performed by examining the title, abstract, and keywords, using the following descriptors: “performance management”, “performance appraisal” and “performance evaluation” combined with the term “effectiveness” and without limiting it to a specific period or journals. The terms performance appraisal and performance management were considered interchangeable; despite their conceptual differences, both terms were included in the search to avoid excluding studies that might use them interchangeably.

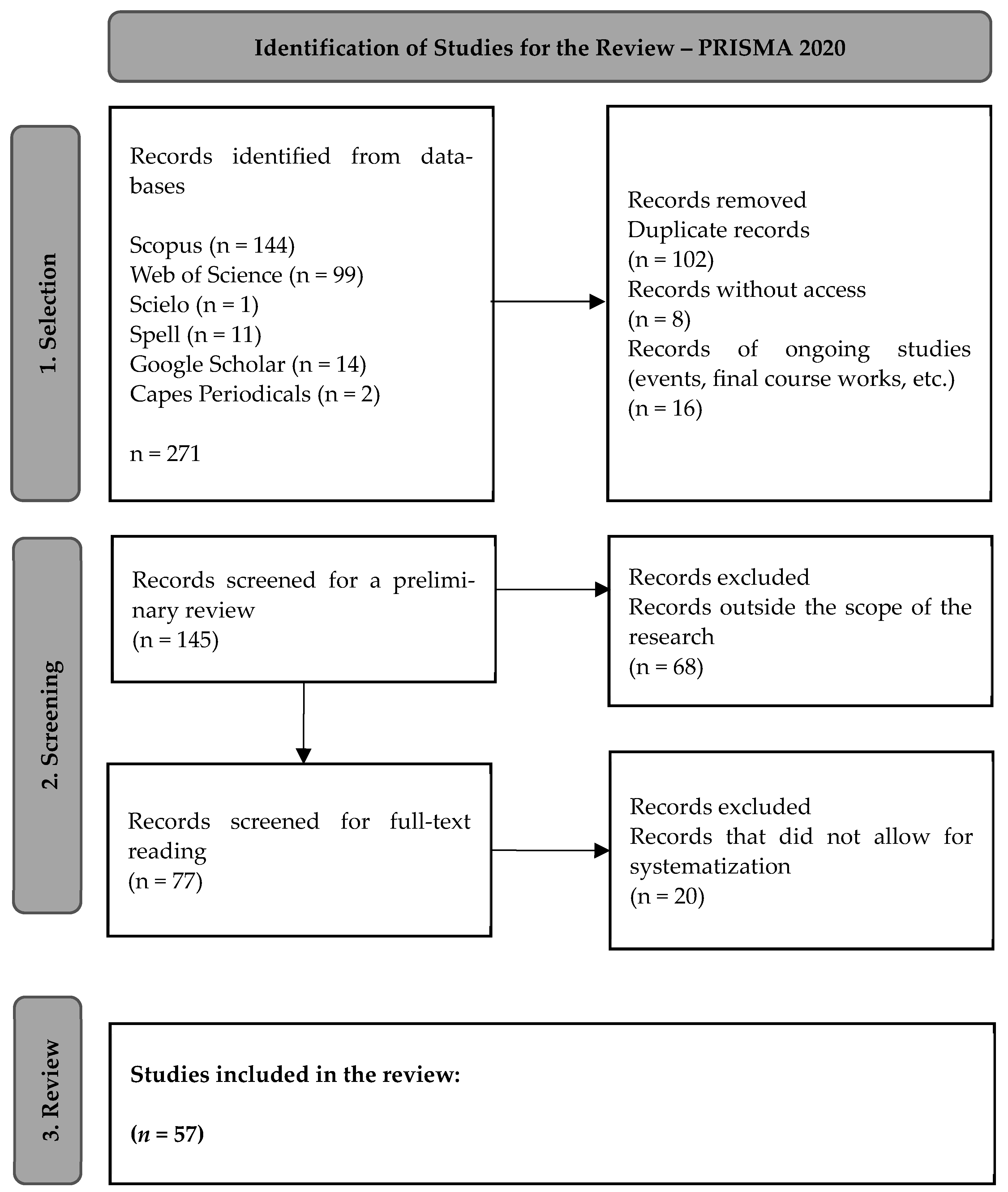

Initially, over 18,000 results were obtained when using these term combinations in the databases. The titles, abstracts, and keywords of the resulting articles from each database were read until no further matches with the search terms were found. Nearly 2000 records were reviewed, resulting in the selection of 271 articles. Subsequently, to ensure transparency and optimize the article selection process (Page et al. 2021), the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines were applied, as shown in Figure 1.

The first filter applied to the identified articles involved excluding duplicate studies, inaccessible studies, and those still under development, resulting in 145 study records. Regarding the decision-making process for including or excluding a particular study, each article underwent initial screening to assess its relevance based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, which unfolded from the object of the literature review (McKenzie et al. 2023). In this way, articles addressing individual PM in the workplace within the framework of HRM policy or practice were selected, while studies on organizational PM were excluded. This decision was made due to the understanding that such studies fall outside the purview of the HRM unit and do not align with the research objectives of this study. Additionally, studies exploring or offering insights into the determinants or factors pertinent to the effectiveness of the performance management system within organizational contexts were included.

Any discrepancies in judgment were resolved through discussion and consensus among senior advisors. Their input, along with additional literature reviews, if necessary, helped inform the final decision. This approach ensured that decisions were made based on a combination of objective criteria and expert judgment, aiming to maintain rigor and consistency throughout the selection process. This step led to the exclusion of 68 articles.

With a sample of 77 remaining articles, a comprehensive reading of the texts was conducted, and the studies were further analyzed. Twenty articles did not provide identifiable criteria or other forms of PMS effectiveness evaluation and were therefore excluded from the sample. Thus, the final sample consisted of 57 articles.

Next, all of the identified criteria adopted in each of the reviewed studies were systematically organized. Initially, the identification was based on the authors’ own statements throughout the text of the reviewed studies. However, when recognition was not possible due to a lack of clarity or the absence of this information, the author of this study analyzed methodological aspects of the study, such as the applied research instrument.

The criteria from the studies were recorded in a spreadsheet. The classification process involved post-categorization content analysis (Krippendorff 2004), and the reviewed studies were consolidated into dimensions and criteria. All of the identified criteria were considered in at least one category, allowing for a frequency examination in this review. The methodological behavior of the studies in evaluating PMS effectiveness was also identified. Operationalization of the studies helped identify measures/variables used to assess the dimensions and criteria as described in previous sections.

After systematizing the scientific production concerning the evaluation of PMS effectiveness, a theoretical-integrative model was proposed, considering the dimensions and criteria identified in the literature in terms of the antecedent-outcome relationship that demonstrates PMS effectiveness. Thus, the arrangement of the model’s dimensions follows the order of the proximity of the outcomes to the PMS.

Initially, the review of the 57 articles allowed for the identification of demographic characteristics, such as the production year and the geographic affiliations of the reviewed authors. Attention to the topic has spanned nearly four decades, with the first reviewed article dating back to 1988 (e.g., Longenecker et al. 1988). In recent years, there has been a significant growth in production, with the last decade accounting for over 70% ( n = 41) of the sample, which indicates a heightened scholarly interest in the subject. The year 2020 stood out as the year with the highest number of articles, with a total of 7 (12%) publications on the subject.

Turning to the geographic affiliations of the authors, the prominence of American contributions underscores the influential role that the United States plays in shaping the discourse on this topic. It was responsible for 17 of the articles (30%), followed by Pakistan with 8 (14%), India with 6 (11%), and Brazil with 4 (9%), with Australia, Belgium, and the UK contributing 3 articles each (5%). Other noteworthy contributors include Canada, Malaysia, the Netherlands, South Africa, and South Korea with 2 articles each (4%), and finally, Bangladesh, China (Hong Kong), Estonia, Iran, Mauritius, Russia, and Vietnam each contributed 1 article (2%).

Evidence of diverse global participation is apparent, with countries such as Pakistan, India, Brazil, Belgium, and Australia making substantial contributions. This international involvement enriches the overall perspective and underscores the universality and global relevance of the subject matter.

The 57 articles analyzed were categorized in six dimensions: financial results, consisting of budgetary, financial, economic, or accounting actions, products, and services (Nankervis et al. 2012); learning, which refers to the knowledge, skills, and attitudes acquired by individuals through their participation in PMS (Schleicher et al. 2019); operational results, referring to the operation of organizational processes; reaction, concerning perceptions about PMS (Keeping and Levy 2000); societal impact, related to the contributions of PMS in terms of what the organization delivers to its external world, including stakeholders (Ikramullah et al. 2016); and transfer, which is related to the ability to transfer results obtained through PMS to work (Schleicher et al. 2019).

We identified 22 criteria and related them to the level of phenomenon analysis (individual/employee, unit/organizational and external environment) of each dimension: reaction, learning, transfer, operational results, financial results, and societal impact. The dimensions are presented in Table 1 in a logical order based on the emergence of PMS results, starting with the most immediate and those closest to the PMS and progressing to those that are less immediate, as presented in PMS result evaluation models (e.g., Dyer and Reeves 1995; Schleicher et al. 2019). The frequency of each dimension and its respective criteria in the studies are indicated. In some cases, the same study adopted more than one because they were not mutually exclusive but rather complementary and used in different arrangements.

The systematization of the reviewed studies demonstrated that the reaction dimension, which was adopted in 41 articles, is the most often used for evaluating the effectiveness of PMS. Similarly, the most adopted criterion by the studies was fairness, used in 24 articles, which belongs to the reaction dimension. In addition to this dimension, the following dimensions were identified: transfer ( n = 34), learning ( n = 26), operational results ( n = 20), financial results ( n = 4), and societal impact ( n = 3).

There is a noticeable tendency in the field to evaluate the effectiveness of the PMS based on the predominance of a specific criterion, in line with the findings of Ikramullah et al. (2016), who state that research has unevenly focused on certain criteria, which can have consequences for both researchers and practitioners by always calling attention to these same criteria. Furthermore, there is a predominance of studies focusing on dimensions related to individual-level phenomena, such as reaction, transfer, and learning, while the organizational perspective, represented by operational and financial results, is less frequently adopted. These results reinforce what Budd (2020), Godard (2014), and Kaufman (2020) term the psychologization of the HRM field, where studies have recurrently focused exclusively or primarily on the internal and micro-organizational perspective to demonstrate the outcomes of HR decisions, even when other measurable non-psychological approaches exist. The following analysis discusses the results of each dimension and the respective criteria adopted to evaluate the effectiveness of the PMS.

The reaction dimension was the most often adopted dimension for evaluating the effectiveness of PM, and it was identified in 41 studies (72% of the reviewed sample). This dimension encompasses the impressions and opinions of organizational actors regarding PMS (Keeping and Levy 2000; Schleicher et al. 2019). Five criteria of the reaction dimension were identified and adopted by the reviewed studies: fairness ( n = 24), accuracy ( n = 20), satisfaction ( n = 14), utility ( n = 13), and affectivity ( n = 8), respectively. These criteria were identified from the reviewed studies and corroborated by the categorization derived from related studies (e.g., Murphy and Cleveland 1995; Schleicher et al. 2019).

The same predominance that was identified in the reviewed studies, evaluating PM effectiveness through the reactions of employees and managers, was previously reported by Schleicher et al. (2019) in their study on PMS effectiveness, as well as the criteria related to reaction, which also appear to be the most adopted for evaluating PM effectiveness. They attribute this current importance as a response to the request made in 1995 by Murphy and Cleveland for a greater focus on reaction criteria, which they considered to be neglected by the PM literature in evaluating PM results and effectiveness. Also, some of the reviewed authors sought to deepen the specific content of this dimension, developing studies that explored reaction as the main element in evaluating PMS effectiveness.

Assessing PMS effectiveness solely based on participant reactions is something used by review studies, and, therefore, it is feasible. However, it is essential to acknowledge that relying solely on the reaction criteria may not fully represent PM effectiveness. A PMS may be perceived as effective by participants, yet it may still contain errors or fail to achieve expected goals. Considering only the reaction dimension only provides a partial evaluation of PM results because other levels or dimensions could have different effects.

Schleicher et al. (2019) reinforce this finding by stating that measuring only this dimension is not enough when determining whether a PMS is successful or not, even though this may be perceived as unjust, inaccurate, unsatisfactory, or useless, and may result in negative feelings and effects. In general, Murphy (2020) points out that among organizations, even if most of their employees do not approve of the PMS, this is not sufficient reason for them to abandon the PMS. Even if excessive concern in terms of avoiding errors makes the system fair and useful, it is not possible to guarantee the desired results; on the contrary, PMS will always be riddled with errors.

It may be concluded that this dimension is based on the perceptions of those involved regarding PMS. This predominance is based both on the nature of the phenomenon encompassed by this dimension and HR’s convenience in accessing this type of information. Considering that these two factors also justify the widespread adoption of this dimension by the reviewed studies and that this may indicate an apparent relevance of the reaction dimension and criteria in evaluating PM effectiveness, the review also revealed a lingering need for greater clarity in the constitutive definition of some criteria to address conceptual confusion, as was pointed out by Murphy and Cleveland as early as 1995. It is essential for studies to correct these conceptual problems due to the predominance of studies that adopt this dimension, especially studies that exclusively adopt or consider this dimension as being essential to evaluating PM effectiveness, to avoid reliability and methodological validity issues.

The learning dimension was the third most adopted dimension for evaluating the effectiveness of PMS, appearing in 31 articles (54% of the sample). This dimension reflects the knowledge, skills, and attitudes acquired by individuals through their participation in the PMS (Schleicher et al. 2019), whether at the end of a cycle or throughout the process. The identified criteria can be systematized into three categories, with attitude being the most adopted ( n = 18) with the highest occurrence among the studies, followed by skill ( n = 17), and knowledge with the lowest occurrence ( n = 13), and all are defined according to the conventional classification of learning in the literature (e.g., Abbad et al. 2019; Kraiger and Ford 2021), which is the same classification used by Schleicher et al. (2019) when they systematized the learning dimension.

It is important to note that the criteria identified here as belonging to the learning dimension were previously mentioned in an isolated or sporadic manner without being associated with a specific group, such as a category or dimension. However, in 2019, Schleicher et al. were the first to classify these criteria within a learning dimension, which then appeared in an effectiveness evaluation model for PM. Therefore, the learning dimension has only recently emerged, and it is primarily differentiated from the reaction dimension, which has been incorporated into the discussion of PM effectiveness evaluations since the 1990s (e.g., Murphy and Cleveland 1995). Thus, the criteria adopted in this review resemble those created by Schleicher et al. (2019), who recognized the importance of this dimension for the PM effectiveness evaluation model and, in the absence of a specific theoretical framework to support the creation of their categories, drew from the established training evaluation literature to propose the learning dimension.

Considering the absence of the learning dimension in previous evaluation models, Schleicher et al. (2019) express some concern that learning has not been addressed in this way in other PMS effectiveness studies and state that without it, it may not be clear how PM achieves its objectives. The authors reference Kraiger et al. (1993) in stating that it is important to differentiate the reaction dimension from the learning dimension to understand PM effectiveness because “reactions capture how the PMS is experienced by employees but are not direct measures of what may have been learned as a result of this experience” (Schleicher et al. 2019, p. 857).

Overall, this review identified criteria in this dimension related to knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSAs) acquired as a result of participation in PMS, including greater clarity in terms of tasks, understanding PMS benefits, developing feedback techniques, and the intention to better behave or act at the workplace. The authors aimed to explain the mechanism by which those reactions transform into other results because reactions alone lack sufficient causal relationships to determine behavioral changes at work as outcomes acquired from PMS participation. While PM effectiveness can be understood through reactions, the issue of learning must also be addressed due to the significant distance between reactions and other behavioral changes transferred at work as PM outcomes.

In summary, the learning dimension is important because it is the first to truly identify the most direct and immediate results of PMS. However, there is still a need to consolidate this dimension for the evaluation of PMS effectiveness, as indicated by this dimension’s proponents in the literature (Schleicher et al. 2019). Furthermore, it is noteworthy that, as predicted by the training literature, a similar logic was employed in the criteria for learning in evaluating the effectiveness of PMS, even though the chosen order of presenting the results in the review of the literature was based on the recurrence of the criteria. Therefore, in a logical order, the first criterion is knowledge, as it is necessary to have clarity about what is expected through the acquisition of information; next is the skill criterion, where the acquired knowledge can be applied; and finally, there is the attitude criterion, which involves a change in intention to behave or act based on what has been learned.

The transfer dimension was the second most adopted dimension among the reviewed articles, appearing in 39 studies (68% of the sample). The reviewed studies assess how PMS can transfer expected individual attitudes, behaviors, and outcomes to work (Schleicher et al. 2019). The transfer dimension in PMS consists of the criteria of job performance ( n = 20), motivation ( n = 18), job attitudes ( n = 16), interpersonal relationships ( n = 11), and well-being ( n = 3).

Although the criteria identified as belonging to the transfer dimension appear in the reviewed studies, it should be noted that this is infrequent and occurs in isolation. Therefore, it should be emphasized that the transfer dimension, like the learning dimension, is of recent origin and emerged in the PM effectiveness evaluation model proposed by Schleicher et al. (2019). It’s important to mention that their intention was not to demonstrate how the application of what was learned is carried out, as envisaged by the training evaluation literature, but rather to show how the multidimensional outcomes of the PMS are expressed in work in a broader sense. Historically, transfer has been neglected as an outcome and has only received attention in recent years. The dimensions described so far are more focused on the context of PMS themselves, that is, how individuals react to PMS and what they directly acquire from participating in PM, but they have not yet been able to demonstrate if and how these criteria results return to work to impact employee behaviors and attitudes (Schleicher et al. 2019). According to these authors, the establishment of this dimension is important as it allows us to understand the attitudes, behaviors, and outcomes that are affected by PMS and go beyond the specific context of PMS by being transferred to work.

Therefore, this study assumes that the transfer dimension encompasses certain criteria that serve as proxy antecedents or outcomes of behavioral changes at the individual level, both conceptually and empirically. In this context, Schleicher et al. (2019) elucidate their transfer criteria, arguing that although the training literature excludes constructs such as attitudes, satisfaction, and motivation from their discussion of KSAOs, these other employee characteristics, particularly when emerging at unit levels, hold economic relevance for organizations. As such, they were considered part of the criteria under individual/employee transfer.

The most prevalent criterion in the transfer dimension was job performance. Many studies linked the effectiveness of PMS to enhancing individual job performance, often assessed through generic questions about how the system affects employee performance. The second most adopted criterion was motivation. While lacking a precise conceptual definition, motivation was often associated with the system’s ability to improve employee willingness to exert effort according to organizational procedures. The authors noted the importance of motivation in achieving organizational goals and reducing turnover. The third criterion was job attitudes, which encompass aspects such as work engagement, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction. The fourth criterion identified was interpersonal relationships, which focuses on improvements in social interactions, particularly between managers and subordinates. Evaluations considered the quality and frequency of these interactions, aiming to establish constructive relationships. The least adopted criterion was well-being, which refers to increased pleasure and reduced suffering at work. Few studies have assessed the impact of PM on employee well-being, considering factors such as the influence of salary on job satisfaction and the system’s ability to boost employee self-esteem.

The relationships established between the criteria of the transfer dimension were based on the Social Exchange Theory, which suggests that positive work outcomes are a form of reciprocation for the investment made by the organization, such as PMS, in their personal and professional well-being, promoting greater engagement and reducing intentions to leave the organization (Kakkar et al. 2020; Sharma et al. 2021). Equity Theory also provides important insights by arguing that perceived equity regarding PMS can increase employee engagement with the organization and work and reduce their intention to leave the organization (Sharma et al. 2021).

These theories were also adopted to demonstrate the importance of reactions in understanding the effectiveness of PMS and were once again used as the theoretical foundations in the reviewed studies to justify the relationships established between the criteria of the transfer dimension and other dimensions that are linked to the field of Psychology (Kaufman 2020). Therefore, this dimension addresses PMS results that are transferred to work and have been identified as being related to performance, motivation, job attitudes, interpersonal relationships, and well-being. In general, the reviewed studies do not specify what is being considered within each of the identified criteria and present them in a comprehensive and generic manner.

Operational results constitute the fourth most adopted dimension and refer to changes in aspects related to the operation of organizational processes (Schleicher et al. 2019). This dimension was adopted in sixteen studies (28% of the sample). The following criteria were identified for this dimension: productivity ( n = 10), turnover ( n = 7), innovation ( n = 6), and workforce ( n = 4). While the previously mentioned dimensions focused on evaluating more immediate results, i.e., those closer to PMS that directly affect individuals, the operational results dimension is the first proposed category to consider results at the unit/organizational level rather than the individual level. This means that the criteria belonging to this dimension can be related to information from HR departments or other departments and can also be applied to data from the entire organization.

It is important to note that the long-term results of PMS are those that are related to organizational performance, moving away from the individual level and approaching them on the macro-level, where individual efforts are aggregated (Dyer and Reeves 1995). Considering criteria on the unit/organizational level is understandable because, in the face of the difficulties in demonstrating the impact of PM models on organizational performance, it is quite enlightening for researchers and convincing for managers to find a significant impact of PM practices and policies on more distant outcomes, such as financial or market performance (Colakoglu et al. 2006). The same occurs with HR policies and practices that are typically linked first to individual outcomes and only later to organizational results, such as operational and financial ones (Paauwe and Boselie 2005).

There is still a lack of robust findings due to the small number of reviewed studies, which hinders a more in-depth discussion of the criteria for assessing PM effectiveness, despite its importance as reported by the studies that argue that PMS could promote organizational outcomes. In this sense, this reflects what was pointed out by Ikramullah et al. (2016) regarding how the literature of various fields prioritizes certain dimensions and disregards others, undermining content that could promote new discussions regarding the topic of interest for other organizational actors (e.g., shareholders, directors).

The penultimate dimension, but the least adopted, was financial results, which consists of aspects related to budgeting, financial, economic, or accounting actions, products, and services (Nankervis et al. 2012), which was adopted in three studies (5% of the sample). Three criteria were identified: profitability ( n = 3), financial Return ( n = 3) and market share ( n = 3).

Financial results also aims to evaluate PMS outcomes at the unit/organizational level. For this reason, financial performance is regarded by the HRM literature as the ultimate raison d’être of an organizational system (Becker and Huselid 1998), and it is frequently adopted in studies that assess the effects of strategic HRM practices (e.g., Huselid 1995; Jiang et al. 2012). This dimension is considered one of the defensible outcomes of a strategic HRM system, as pointed out by Dyer and Reeves (1995), along with operational outcomes and those related to HRM. Thus, this study is often referenced to justify the adoption of strategic HRM systems (e.g., Colakoglu et al. 2006; Paauwe and Boselie 2005).

In the PM literature, this dimension is still relatively underexplored, as may be inferred from the small number of studies that have evaluated PMS results based on financial outcomes and have also not conducted in-depth examinations of this dimension. The most prevalent criterion is profitability, which signifies the financial gain obtained by the organization, excluding taxes, costs, and expenses. This criterion has been consistently adopted by four studies: Abdullah and Abraham (2012), Nankervis et al. (2012), and Schleicher et al. (2019). The studies focused on assessing the financial performance of organizations based on their net gains, providing a key metric for evaluating PMS effectiveness.

Two additional criteria, financial return, representing the financial gains after an investment, and market share, indicating the portion of a specific product or service that the organization holds in the market, were considered by the same three studies, which constituted 5% of the reviewed studies: Nankervis et al. (2012), Schleicher et al. (2019), and Stanton and Nankervis (2011). Regarding financial return, Nankervis et al. (2012) and Stanton and Nankervis (2011) included return on investment as a variable, reflecting the return to the organization from the investment made. This metric was also identified in Schleicher et al.’s (2019) review. Market share, which assesses the organization’s presence and dominance in a specific market segment, was evaluated by Nankervis et al. (2012) and Stanton and Nankervis (2011) and included in Schleicher et al. (2019) as market competitiveness.

These studies established few relationships between the previous dimensions and financial results, as well as between financial results and the other identified dimensions. This can be partially attributed to the perspective adopted by some of the reviewed studies that consider operational results and financial results to be “Organizational Results” (e.g., Nankervis et al. 2012), suggesting that the established relationships can also be interpreted as part of the financial outcomes of the operational results.

The operationalization of this dimension occurred on an individual level, utilizing subjective measures. Thus, there is a predominance of individual measures for assessing phenomena on the macro-organizational level, as pointed out by theorists discussing the process of psychologization (e.g., Budd 2020; Godard 2014; Kaufman 2020). Similarly, the use of financial indicators for measuring results has also been in use since the 1990s in HRM policies and practices (Wright and Ulrich 2017). However, its use was already being questioned and regarded as problematic due to its interrelation with other factors that do not involve solely the HR unit’s performance (Paauwe and Boselie 2005). Furthermore, even though these authors study outcome evaluations (e.g., Wall et al. 2004) and suggest that studies incorporating organizational financial results should strive to use objective measures instead of subjective ones, they continue to employ subjective measures. This behavior is also identified by Wall et al. (2004), who provide important insights into the relevance of objective measures, particularly in relation to financial results and indicators.

The last dimension, societal impact, was represented by four studies (7% of the sample). This dimension refers to the contributions of what is planned and delivered by the organization to its external world, including society, customers, suppliers, and other stakeholders (Ikramullah et al. 2016). The four reviewed studies evaluated PMS based on customer satisfaction. The societal impact dimension identified in the reviewed studies provides information about the outcomes achieved on the highest level of evaluation and, consequently, the one furthest from PMS. When referring to this level, it is important to note that this dimension goes beyond the organizational level and is therefore mentioned in the evaluation literature as the mega-organizational level and addresses what is planned and delivered to the primary beneficiaries, such as consumers or citizens (Kaufman and Keller 1994).

This dimension seeks to fill a research gap in PM evaluation by including aspects of the external environment (Kaufman 2020; Jiang et al. 2013) and involving stakeholders beyond those internal to the organization (Colakoglu et al. 2006). While the term impact appears in some other evaluation models, it is often mentioned in relation to work impact, as some authors in the PM training and outcome evaluation literature tend to refer to it, or simply as a generic statement indicating that the PMS outcomes have an impact on the organization. It is important not to confuse the societal impact dimension identified in this study with the previously mentioned dimensions.

The societal impact of PMS is overlooked by most of the reviewed studies, as previously noted in studies on HRM policies and practices (e.g., Dyer and Reeves 1995). An evaluation of effectiveness should extend beyond individual-level changes to the promotion of improvements at the environmental level at which the organization operates. This may be attributed to the distance of this dimension from PM practices, which makes its evaluation challenging without the application of rigorous statistical techniques that can establish causal relationships.

The dimensions and criteria were adopted in combination, as the majority (74%) of the reviewed studies used more than one dimension to evaluate PM effectiveness. The simultaneous adoption of different dimensions is one of the main findings of this review, as it enriches the discussion of the need to consider various measures to assess PM effectiveness. This result is in line with the existing literature, and authors acknowledge that it is not possible to define a best criterion to measure effectiveness due to its multidimensional nature (Ahmed 1999; Ikramullah et al. 2016; Iqbal et al. 2015, 2019; Keeping and Levy 2000; Lawler 2003; Schleicher et al. 2019). Therefore, conducting a study aimed at evaluating PM effectiveness based on only one dimension or criterion means disregarding other results of the PM system that contribute to effectiveness.

The multidisciplinary nature of the effectiveness construct also sheds light on how each adopted result for evaluating the PM system may vary depending on the needs, values, and preferences of stakeholder groups within the organization, which further complicates determining PM effectiveness (Colakoglu et al. 2006; Ikramullah et al. 2016). Therefore, it should be emphasized that an analysis based exclusively on the quantitative results from a systematic review of the literature is not enough to address the concerns of both academics and practitioners. The fact that the reaction dimension was the most frequent among the reviewed studies does not imply that evaluating it exclusively would provide a comprehensive measure of PMS effectiveness. Similarly, it cannot be assumed that the least adopted dimension, societal impact, does not provide insights into PM effectiveness.

A literature review aims to, first of all, quantify the frequency of adoption for each dimension or criterion (Table 1) and, based on that, provide an overview of how the reviewed studies make choices regarding the evaluation of certain dimensions and criteria over others. It also identified the obtained results, as well as the general techniques and methodological behavior.

The identification of the methodological behavior of studies demonstrates that studies have predominantly assessed PMS effectiveness by using measures on the individual level that are of a subjective or perceptive nature (e.g., Longenecker et al. 1988; Sharma et al. 2021). Therefore, as a result, somewhat due to the larger number of studies adopting these dimensions, the adoption of scales or instruments to assess PM effectiveness has been more evident in dimensions whose phenomena are examined on an individual level.

There is a noticeable convergence in the assessment of the reaction dimension, especially in terms of the combined measurement of justice and accuracy criteria to assess PMS effectiveness in recent studies (e.g., Awan et al. 2020; Modipane et al. 2019; Sharma et al. 2021). Regarding the learning dimension, the attitude criterion stands out as the most adopted and is notable for being measured in relation to the intention to continue working at, or leaving, an organization, as demonstrated by three studies (Kakkar et al. 2020; Sharma et al. 2021). In relation to transfer, the last dimension on an individual level, although the job performance criterion is the most adopted, followed by the motivation criterion (the second-most adopted), the application of a specific scale for its evaluation was not observed in the reviewed studies; instead, it appears only as items in the instruments assessing PM effectiveness (Iqbal et al. 2019; Kakkar et al. 2020; Sharma et al. 2021; Upadhyay et al. 2020).

Most studies considered dimensions or criteria whose phenomena are on an individual or organizational level and are internal to the organizational environment (e.g., workforce characteristics, turnover). This finding is troubling due to the acknowledged need for an integrative and holistic perspective where both internal and external aspects should be considered to evaluate the many ways in which PM can influence organizational performance (Ikramullah et al. 2016).

The adoption of dimensions and criteria that are internal to an organization is related to the logical order in which the PM effectiveness evaluation dimensions were identified and positioned in relation to PMS. This is because the dimensions are arranged from the most immediate and closest to PMS to the less immediate and more distant ones, as presented in PM effectiveness evaluation models (Levy and Williams 2004; Schleicher et al. 2019) and in models that aim to measure the effectiveness of HR policies and practices (Dyer and Reeves 1995; Kaufman 2020). Establishing the relationships between PMS and these dimensions, particularly more distant ones, such as social impact, proves to be a complex and challenging endeavor. This difficulty has compelled studies to focus on evaluating dimensions that are closer to PMS and are considered to be more accessible (Ikramullah et al. 2016; Schleicher et al. 2019).

Given the position occupied by the dimensions, it is important to highlight that PMS, even though they are aimed at organizational performance, as stated in theoretical models and the purpose of PMS itself, are at best behavioral shaping tools to enhance worker productivity. Later, other variables, both individual and contextual, come into play, which affect the relationship between the dimensions identified as individual phenomena and those on the unit/organizational level (operational, financial, and societal), thereby increasing the difficulty of measuring causes and effects. Experimental studies can and should assess this.

The literature still relies on the need to confirm that PMS indeed influence individual-level phenomena (reaction, learning, and transfer), that is, they act as a tool that can modify individual behaviors to promote superior organizational performance. Thus, the reviewed studies have sought at certain moments to demonstrate specific causal relationships by relating the adopted criteria and their respective dimensions. These relationships are presented further and are part of the construction of the proposed theoretical-integrative model.

The proposed theoretical-integrative model for evaluating PMS effectiveness is based on the relationships between the reviewed dimensions and criteria. In addition, both of the PMS effectiveness evaluation models covered in this review (e.g., Ikramullah et al. 2016; Iqbal et al. 2015; Keeping and Levy 2000; Schleicher et al. 2019) and the models for evaluating multilevel SHRM outcomes (e.g., Jiang et al. 2013; Jiang and Li 2019) were used as references.

The dimension identified as the most immediate is reaction. Its position is based first of all on its definition and nature, because it provides authors with an understanding that this is the way in which PMS participants can most clearly perceive the system’s benefits (Keeping and Levy 2000; Levy and Williams 2004). Secondly, HR departments find it convenient to access this type of information through surveys that directly measure participant perceptions, given that this is an individual level phenomenon that can be easily obtained through individual-level measures.

The literature reviewed indicates that reactions are theoretically related to PMS acceptance, and perceived fairness on the part of the system will contribute to its greater acceptance and result in organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Furthermore, fair systems are linked to providing useful feedback, which affects employee motivation, commitment, and performance. PM satisfaction is also related to providing employees with adequate information about the system and organizational expectations. To sum up, the reaction dimension is linked to the learning dimension and indirectly linked to the transfer dimension through learning. No direct relationships were found between the reaction dimension and other organizational-level dimensions.

Regarding the learning dimension, reactions alone are not sufficient to determine what has been acquired due to participation in the PM system. Due to the significant distance between the reaction dimension and understanding how PM results are transferred to work, the causal path of relationships requires addressing the learning dimension to explicitly demonstrate PM effectiveness.

This review identified criteria within the learning dimension that address the outcomes resulting from employee participation and interaction in PMS. These outcomes include task clarity, understanding the benefits of the system, developing skills for giving and receiving effective feedback, and changes in work-related behavioral intentions. The provision of effective feedback, especially when positive, is related to activating goal-related orientation, which can facilitate PM satisfaction (Culbertson et al. 2013). The development of managerial skills in the PM process also contributes to achieving better results (Haines and St-Onge 2012).

PMS can be evaluated through changes in employee actions and attitudes that lead to positive organizational outcomes, and the participation of those being evaluated in the PM process is encouraged to create consensus and reduce conflicts, resulting in greater satisfaction and commitment (Ikramullah et al. 2016; Lawler 2003). Acceptance of PMS is influenced by perceptions of fairness and clarity regarding the system, which affect organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and trust in superior-subordinate relationships (Abdullah and Abraham 2012; Roberts 1992). The development of managerial skills through PM has also been found to positively affect organizational commitment, job performance, and the intention to continue working in the organization (Van Waeyenberg and Decramer 2018).

These relationships in the learning dimension criteria demonstrate a causal link that begins with knowledge acquired through enough information, which, when applied, is referred to as skills and is expressed through intentions to act or behave, which are represented by attitudes. The learning dimension is important because it is the first to signal the most direct and immediate results of PMS, which are directly preceded by the reaction dimension. Learning is related to transfer and indirectly related to organizational-level outcomes, such as operational results and financial results.

In evaluating the effectiveness of the Performance Management (PM) system, the transfer dimension is related to job performance, which is the behavior exhibited at work that aims to achieve organizational results. Job performance is linked to the PMS’s purpose, which is to align individual performance with organizational objectives to drive overall organizational performance (Aguinis 2013). Job performance is related to the acceptance of PMS, skill development, employee motivation, increased productivity, and reduced absenteeism (Mok and Leong 2021; Roberts 1995). Studies have shown that motivation positively influences productivity and target audience satisfaction, which affects organizational performance (Biulchi and Pauli 2012).

Furthermore, effective feedback plays a key role in promoting motivation at work and is recognized as an effective practice for enhancing employee motivation (Awan et al. 2020; Iqbal et al. 2015; Lawler 2003; Soltani et al. 2003). Job satisfaction is also a commonly related outcome of PMS transfers (e.g., Mok and Leong 2021; Schleicher et al. 2019; Upadhyay et al. 2020). PMS is seen as part of a social context in which organizational members perceive it as promoting professional growth and well-being. This positively affects work attitudes, such as satisfaction and commitment, and influences intentions to stay at an organization or leave it (Kakkar et al. 2020). Thus, the transfer dimension is preceded by the reaction and learning dimensions and has a direct relationship with the organization’s operational results. Although no impact on financial results was mentioned, they have an indirect relationship with Social Impact.

The operational results dimension is the fourth dimension in evaluating PMS effectiveness, and it considers outcomes that occur on the unit or organizational level rather than the individual level. This dimension has more long-term consequences, and as a result, its outcomes may appear less accessible to organizational actors. However, it is enlightening for researchers and managers because it demonstrates the significant impact of PM practices and policies on organizational outcomes, even if these outcomes are more distant and influenced by other factors (Colakoglu et al. 2006).

The operational results dimension relates its criteria to increased productivity in organizations and establishes a positive relationship with the public’s perception of improved service quality (Nankervis et al. 2012). Turnover is also evaluated as an effectiveness criterion for PM, and it is related to feelings of happiness or distress at work in response to rewards or sanctions within PMS such as dismissals (e.g., Espejo et al. 2021). Regarding the operational results dimension, the relationships established between the operational results division and other unit/organizational-level dimensions have not been extensively explored in the literature, which reflects a point made by Ikramullah et al. (2016) regarding how fields prioritize certain dimensions and disregard others, thus subverting content that could promote new discussions. Thus, the operational results dimension is positioned directly after the transfer dimension and has an indirect relationship with social impact. The relationship with financial results has not been explicitly identified in the reviewed studies as the others have, but based on the integrative model proposed by Schleicher et al. (2019) and the literature on general performance (e.g., Dyer and Reeves 1995), it is understood that operational results have a direct relationship with financial results.

The penultimate and sixth dimension identified is financial results, which is still rarely addressed in the PM literature, as can be inferred from the number of studies that evaluated PMS results but did not extensively study this dimension. Therefore, the financial results dimension is indirectly preceded by the other dimensions described so far and is directly preceded only by operational results. Finally, the sixth dimension identified is social impact. It is noteworthy that this dimension has been disregarded by a substantial portion of the reviewed studies and appears in only four studies, one of which mentions it only theoretically. It is alarming that this dimension does not appear, considering that an evaluation of effectiveness goes beyond changes on the individual and internal levels of the organization and also includes promoting improvements within the organization’s social context. This disregard may be due to the distance of this dimension from PMS, making its evaluation statistically risky without the application of rigorous techniques that can establish minimal causal relationships.

For the construction of our model, the evaluation of PM effectiveness occurs on three different levels: individual, organizational, and environmental. The model starts with the micro-level, which refers to the individual level, whose results are more immediate and proximate to PMS, then considers macro-level dimensions, which refer to the unit/organization, and finally considers the environmental/societal level, where the results are the most indirect and distant from PMS. Figure 2 represents the PMS theoretical-integrative effectiveness evaluation model.

By establishing these relationships, this study seeks to assess the relationships between the individual dimensions and PMS and evaluate whether they cause changes in individual behavior. While PMS seeks to promote superior organizational performance, as identified in the reviewed literature and embodied by the proposed integrative model, the central premise of the PM model is that PMS is capable of affecting individual behavior at work, as represented by the transfer dimension. For this purpose, we chose to use measures that have already been constructed and can be adapted, and whose recurrence in the literature makes them more consolidated. By recognizing the impact of PMS on individual behavior, it becomes possible to include other dimensions that are more distant from these systems to assess their unit/organizational-level results. As Schleicher et al. (2019) found, although most studies demonstrate a positive impact between PMS and organizational performance, the methods and types of measures applied appear to be problematic for drawing clear conclusions.

It is in this context that Kaufman (2020) summarizes the measurement of HRM system results, as seen in the case of PM, as “centered on an unproductive, nearly universalistic paradigm, guided by quantitative methods, with poorly developed and measured HRM system concepts, and a tattered set of practical implications and outcomes”.

According to the integrative theoretical model that reflects established relationships, dimensions related to the individual phenomenon follow this order: the reaction dimension is directly linked to the learning dimension and is also related to the transfer dimension, but only indirectly through the learning dimension. Within this context, the learning dimension is preceded by the reaction dimension and directly linked to the transfer dimension. Finally, the transfer dimension is directly preceded by the learning dimension and indirectly preceded by the reaction dimension.

In this sense, this study proposes relationships between individual dimensions and PMS to assess whether there are indeed changes in individual behavior. In view of this panorama, the authors Budd (2020) and Kaufman (2020) emphasize the importance of shifting the focus of HR results towards a less universalistic perspective and producing theoretical frameworks that are specific to HRM, as the founders of the SHRM field did (e.g., Huselid 1995; Lawler 2003; Wright and McMahan 1992), understanding systems as being open, generalist, and configurational with plural interests, including the practical and professional experiences of the field’s researchers. The proposed integrative theoretical model seeks to promote a holistic and integrated view of the multiple dimensions that usually make up the construct of effectiveness in the PMS evaluation process.

The purpose of this study has been to propose an integrative model to evaluate the effectiveness of the performance management system (PMS) by systematizing the dimensions and criteria adopted by the literature and tracing the causal relationships indicated by the authors. Our review also identified the methodological patterns adopted by these studies to assess PM effectiveness, which resulted in the identification of the subjective and objective measures employed on the individual and unit/organizational levels.

We have also sought to highlight the importance of dimensions that have been recurrently adopted, such as those whose phenomena occur on the individual level, to resolve the current conceptual confusions that have been reported. This article is also expected to advance the study of dimensions that, as identified, do present results regarding the positive impact of PMS on organizational performance but are methodologically weak or unproductive and seek to promote new theoretical and methodological discussions about the topic.

The construction of a PM effectiveness evaluation model has many potential applications. It may be of interest to academics and provides a novel approach that goes beyond this field’s universalistic tendency and expands the development of SHRM theories. We recommend a future research agenda focused on conducting rigorous empirical studies to test the outlined relationships. This approach will help advance the understanding of the relationships between these individual dimensions, the PM system, and organizational outcomes, thereby contributing to the enhancement of performance management practices and the expansion of theoretical knowledge in this field. It may also meet the needs of practitioners by providing insights into PMS results that would be of interest to HR departments.

One limitation of this model is the absence of contextual or input variables, as employed in some PM effectiveness evaluation models (e.g., Schleicher et al. 2019; Ikramullah et al. 2016). These models consider aspects such as technology, organizational structure, culture, and the reputation of HR departments, which are identified as influencing factors in the PMS process. However, this integrative theoretical model considers dimensions and criteria to access the antecedent-result relationships that manifest PM effectiveness, as pointed out by Iqbal et al. (2015), which can be evaluated further.

An additional constraint arises from our review’s objective of exploring the Brazilian literature and juxtaposing it with international sources. However, the outcomes did not include solid Brazilian research, which may have been due to a paucity of studies. As a result, it is imperative that forthcoming investigations undertake a comparative analysis between this international review and Brazilian reviews of the literature and the literature of various individual developing countries and regions. Such an undertaking will be crucial to evaluating the congruence of global agendas and facilitating the establishment of a comprehensive base of knowledge, which, as indicated above, is currently characterized by a dearth of integrative studies.

Conceptualization, M.L.d.A., A.L.M.S., C.N. and P.P.M.M.; methodology, M.L.d.A. and P.P.M.M.; software, M.L.d.A., L.S.C. and B.S.B.; validation, M.L.d.A., P.P.M.M., J.C.d.S.S. and L.C.R., formal analysis, M.L.d.A., L.S.C. and P.P.M.M.; investigation, M.L.d.A.; resources, M.L.d.A.; data curation, M.L.d.A., L.S.C., B.S.B. and P.P.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.d.A.; writing—review and editing, L.S.C., N.M. and P.P.M.M.; visualization, N.M.; supervision, P.P.M.M. and A.L.M.S.; project administration, P.P.M.M., A.L.M.S. and C.N.; funding acquisition, M.L.d.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research was funded by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes), Brazil (88887.597228/2021-00). The APC was funded by Fundação de Apoio à Pesquisa do Distrito Federal, Brazil (00193-00001098/2023-61).

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Figure 1. Diagram used for the systematic review of the literature. Source: Adapted from Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Page et al. 2021).

Figure 1. Diagram used for the systematic review of the literature. Source: Adapted from Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Page et al. 2021).