The Family Security Act 2.0 (FSA 2.0) framework introduced this past June by Senators Mitt Romney (R-UT), Steve Daines (R-MT), and Richard Burr (R-NC) emerged as negotiations over extending the 2021 expanded child tax credit stalled. While FSA 2.0 would leave many families better off, others – particularly single parents – could actually face a tax increase due to the proposal’s fiscal offsets.

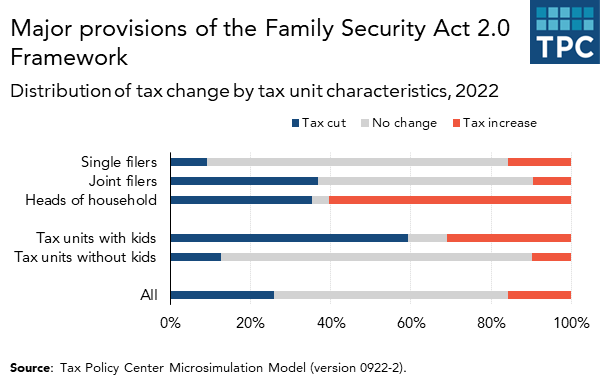

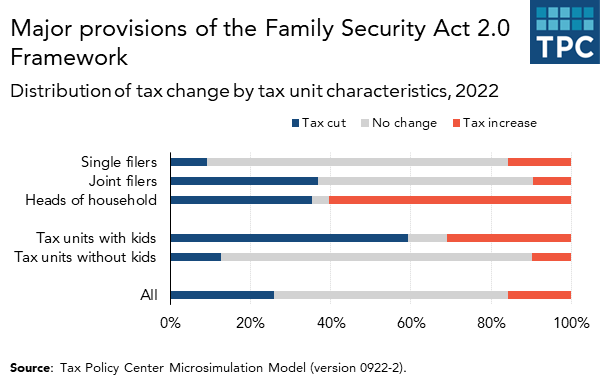

According to new Tax Policy Center estimates of major elements of the FSA 2.0 framework, benefits would increase for nearly 60 percent of families with kids relative to current law, while taxes would be higher or benefits lower for just over 30 percent of families with kids. More than 85 percent of the families with kids whose taxes would increase are headed by single parents who file using head of household status. Joint filers across the revenue distribution receive tax cuts at similar rates, while benefits for single and head of household filers are limited to those with lower incomes.

FSA 2.0 would replace the current child tax credit of $2,000 with a child allowance of up to $4,200 per child under age 6 and $3,000 per child ages 6 to 17. Although the child allowance would not be fully refundable, like the 2021 CTC, it would phase in more quickly than the current CTC. Right now, families could need as much as $30,000 in earnings, depending on their filing status, to receive the maximum CTC. Under FSA 2.0, families would only need to have at least $10,000 in earnings to access the maximum benefit, and those with less than $10,000 in earnings would receive a partial benefit. The $10,000 earnings requirement would apply to tax units headed by both single and married parents.

FSA 2.0 retains the current requirement that children have valid Social Security numbers (SSNs) to qualify for the CTC and would add that requirement for their parents. This change would affect CTC eligibility for parents who file with Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITINs), who are typically immigrants.

FSA 2.0 would also provide expecting parents with monthly payments of $700 during the last four months of a pregnancy. However, due to data limitations, we were unable to model that provision. We also assume all families receive the child allowance as an annual lump sum payment based on their most recent year of income. If enacted, the child allowance would be distributed by the Social Security Administration, and parents could choose to receive it monthly based on their prior year’s income. Unpredictable changes in income and household composition affect many low-income families and could impact eligibility for child allowance benefits.

The cost of the child allowance would be offset, in part, by restructuring the earned income tax credit (EITC) and eliminating several other tax benefits. EITC benefits would increase for filers without qualifying children at home and decrease for those with children at home. Maximum benefits would be higher for married filers than unmarried filers. Whether the increased child allowance offsets the decreased EITC for tax units with kids would vary based on how many of the kids in the tax unit are under the age of 6, and whether the tax unit is headed by a single parent or married couple.

Several tax benefits would be eliminated:

Taken together, we estimate that these provisions would offset $66 billion of the $108 billion cost of the child allowance in 2022. If implemented, the framework as a whole would have reduced revenues by approximately $42 billion in 2022.

See our companion analysis of the anti-poverty effects of FSA 2.0 compared with an extension of the 2021 CTC, for more details about the framework and assumptions used in our modeling.